Blog

What Does “Noninstitutional Design” Mean For Behavioral Health?

Most design guides recommend a “noninstitutional” aesthetic for fixtures and furniture in behavioral health facilities, often in the context of recommending “therapeutic” design. But what does that really mean? How can designers and specifiers make that choice objectively?

Here at Visa Lighting, we’ve developed each behavioral health luminaire with therapeutic design in mind—so we know what it means to us as manufacturers. In this blog post, we’ll overview the basics of institutional vs. therapeutic design, highlight the positions of three major design guides, and explore what these ideas mean for patient experience.

What is “institutional design”?

Institutional buildings (healthcare, education, recreation, public works, etc.) are not necessarily institutional-looking; however, the term is often used to mean the opposite of home-like. It may indicate a sterile, cold environment. An institutional luminaire might be relatively large, have a bulky housing, exposed fasteners, or an angular form factor. At best, institutional fixtures are totally appropriate for a conference room or school hallway—but you wouldn’t want one in your bedroom.

Behavioral health facilities need furniture and fixtures to be tamper-resistant, impact-resistant, and ligature-resistant (which means that fixtures cannot be used to anchor a rope or loop of fabric). Light fixtures contain electrical components and are often within a patient’s reach, so they are often under scrutiny as a potential opportunity for ligature or damage. Because of this, designers and facilities staff have had to choose luminaires meant to withstand high impacts and tampering. For a long time, their only options had been originally designed and marketed for correctional institutions.

However, design should be determined by the function of a space, and the shapes and materials we choose often signal the activities a given space is meant to accommodate.

Why is institutional design undesirable in behavioral health spaces?

Behavioral health facilities provide treatment and recovery for patients with behavioral and mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, dementia, substance addiction, eating disorders, and more. Many of these conditions may have symptoms that require temporary or long-term inpatient care, like suicide ideation or attempts, aggression, self-harm, psychosis, or difficulty with executive function.

Environments that alienate patients and make them feel watched, judged, or isolated can aggravate those symptoms. Recent guidelines and standards strongly recommend therapeutic design in behavioral health settings---especially for inpatient facilities, where patients can spend an average of 7.2 days.

Being admitted to inpatient care can be stressful, especially after a crisis event. We have a responsibility to avoid design elements that trigger or exacerbate things like hopelessness, feeling trapped, isolation, feeling like you’re being watched, guilt, shame, sensory overload, and boredom. We can intercept those feelings through elements of the design that invoke freedom, connection to nature, creativity, privacy, individuality, self-control, environmental control, social control, and more.

What do the experts recommend?

As early as the 1970s, designers and healthcare professionals have been advocating for behavioral health facilities to be homelike and conducive to socialization. Throughout the mid-1900s, deinstitutionalization efforts by the government meant less funding allocated for new facilities or renovations ("Deinstitutionalization" was an international trend of closing down and defunding public behavioral health institutions that spanned the second half of the 20th century). The only places where you would typically see therapeutic design was in privately owned rehabilitation centers.

Today, designers have access to several guides, standards, and research reviews written by experts in the field. However, nothing is 100%; there’s no direct line between one design element and a particular patient outcome. Since patient data must remain private, studies often rely on post-discharge patient surveys and interviews with staff. By keeping up to date on all these resources, designers and manufacturers can make informed design decisions for a given facility according to the patient groups who will be treated there.

This is what the major guidelines have to say about noninstitutional, therapeutic design:

Patient Safety Standards, Materials, and Systems Guidelines - NYSOMH and architecture+

In the Patient Safety Standards guide published by the New York State Office of Mental Health and architecture+, “Therapeutic Environment & Appearance” is listed as a secondary criterion for product evaluation. Each product in this guide is labeled by its appropriateness for low risk, medium risk, and high risk areas. “Though high risk products may be safe for all areas,” the guide states, “they may not be appropriate for all areas. In many cases the high risk product will look too institutional for the area.”

This is an important aspect of behavioral health design to highlight. Risk level is not a flat characteristic across the whole facility. While noninstitutional products should be used wherever possible, they don’t need to be as robust in areas with constant supervision and few opportunities for self-harm. This brings us to our next guide, which contains a helpful resource to support design teams in finding the right product for each area.

Behavioral Health Design Guide - Behavioral Health Facility Consulting

Regularly updated by experts in the field, the Behavioral Health Design Guide published by BHFC (formerly by NAPHS and FGI) repeatedly calls for non-institutional furniture and fixtures that can hold up to safety standards. Like we mentioned above, the BHFC includes in this document the Patient Safety Risk Assessment Tool, a comparative matrix that weighs a patient’s intent for self-harm against their opportunity for self-harm. Design teams can apply this measurement to any area and come to an immediate decision about which level of products should be specified.

This tool allows designers and medical staff to consider aesthetics right alongside safety, which is more difficult to accomplish when looking at all the variables one at a time. “The focus on patient and staff safety has often pushed the aesthetics of these units toward the appearance of a prison environment,” the guide states. “The challenge is to strike a balance between the safest possible healing environment and a non-institutional appearance that is correct for the unique conditions that exist in each facility.”

For example, the guide strongly discourages the use of traditional 2’x2’ or 2’x4’ ceiling fixtures, which look very institutional, especially in patient bedrooms. This “is a carryover from general hospital design that is seldom needed in behavioral health facilities.”

Mental Health Facilities Design Guide - VA

The Mental Health Facilities Design Guide is published by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Construction & Facilities Management. The introduction of this document summarizes the underlying reason for therapeutic design quite well: “Facility design impacts the beliefs, expectations, and perceptions patients have about themselves, the staff who care for them, the services they receive, and the larger health care system in which those services are provided.”

The second of ten guiding principles for the guide states that behavioral health facilities should be a “therapeutically enriching environment,” which means that the design should be:

- Homelike

- Familiar

- Provide visual and physical access to nature

- Allow patient autonomy, respect, and privacy

Therapeutic design has the power to “imbue healing, familiarity, and a sense of being valued.” By establishing these values early in a guide that will discuss both safety and comfort, the VA makes clear that you cannot have one without the other. Therapeutic design in behavioral health settings can have the following impacts:

- The sense of being valued

- Better connections between staff and patients

- Positive socialization

- An emphasis on recovery rather than monitoring symptoms

- Place attachment, a sense of calm attachment to one’s surroundings

- Patients who will continue to seek out treatment if their experience is positive

Where do we go from here?

Options have grown and the manufacturing industry is more knowledgeable about what’s needed in this area. Comfort doesn’t need to be a secondary concern. It is possible to make something that is both safe and therapeutic. If a patient’s environment can have a direct impact on their well-being, the design mandate “do no harm” becomes all the more imperative, and the term “noninstitutional” becomes less subjective.

How we interpreted "noninstitutional" for our behavioral health/high impact luminaires

Visa Lighting’s behavioral health collection began when healthcare architects expressed the need for an attractive ceiling luminaire. We took our Serenity family, originally designed for general healthcare, and modified the recessed 2’x4’ and 2x2’ ceiling models to have an additional polycarbonate lens secured with tamper-resistant fasteners. Serenity’s multifunctionality and shape fulfilled the functional needs of a behavioral health facility, but unlike the traditional 2x2 or 2x4, it was the calming decorative panels and luminous glow around the edge that made Serenity ideal for therapeutic environments.

Later, Sole was developed. Our product designers began exploring options for a behavioral health vanity luminaire. They noticed that mirrors used in this market are typically rough-looking and not very reflective, so they decided to build our own with integrated lighting. To make the patient bedroom and bathroom a more comfortable environment, we designed Sole to 5-star hotel standards. The bathroom is where patients spend the most time alone, especially if they share a bedroom. We wanted patients to feel relaxed and valued, so we designed the mirrored surface and its light source to produce pleasing light and an accurate reflection.

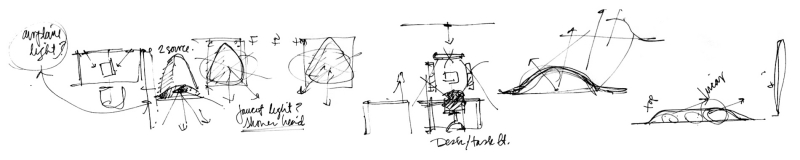

Gig was designed after a brainstorming session with behavioral health architects and designers at our Innovation Lodge trip. They wanted a reading light that could be mounted on the wall—which was a challenging product to find for behavioral health. The original concept, as you see below, followed Gig all the way to the factory floor. We were able to mimic the shape of behavioral health showerheads, so the luminaire slopes outward from the wall in one smooth line and angles the light down. By having one unbroken texture through the whole housing, and by keeping the fixture a compact size, we created a minimalist, personal luminaire that could serve each patient individually. Gig’s capacitive touch-dimming controls were integrated to give patients an added sense of control over their environment.

Symmetry has been on the market since 2016, with models designed specifically for patient overbed, general use, and tunability. They feature a patented concave dome in the center of the lens and 23” or 45” diameter options. Symmetry's six new behavioral health models were designed to retain everything that made Symmetry unique and beautiful. The tamper-resistant screws that fasten the frame and lenses to the ceiling structure are barely visible and painted with the same finish as the frame. This keeps the aesthetic as minimalist as possible. The outer frame was redesigned with a marginal increase in thickness. Additionally, the secondary polycarbonate lens is completely clear, which allows the inner acrylic lens to produce the same illumination effect.

Coming soon, we’ve also modified our Visage and Lenga families to include new behavioral health models. With every one of these luminaires, we worked hard to retain the original aesthetic and design intent.

What does the future look like?

Therapeutic design isn’t just about behavioral health, it’s related to design movements like WELL, patient-centered design, circadian lighting, and more. In almost every area, we’re paying more attention to how the built environment impacts our physical and mental health.

Additionally, behavioral health design experts urge specifiers and medical staff to think about co-occurrence. Up to 45% of people admitted to the hospital with a medical issue have a co-occurring behavioral health condition. In fact, recent Joint Commission guidance clarifies that ligature points and other “self-harm environmental risks” must be identified and removed from all areas of the hospital unless they are necessary for the treatment of the patient.

The United States has had a shortage of behavioral health facilities until very recently. As new buildings are constructed, and as the architectural community becomes fluent in behavioral health best practices, we will all have more conversations about the minutiae of therapeutic design. Hopefully there will be more post-occupancy studies to reference; in particular, we hope more studies will discuss the perspectives of specific patient populations and their environmental needs.